The recent cascade of public revelations by women who were sexually harassed or assaulted by popular societal figures whose behavior was allowed to continue unchecked for, in some cases, decades, bears a striking resemblance to a case that occurred in the spring of 1900 in Santa Rosa, the county seat of Sonoma. It is the case of a prominent doctor, Melville M. Shearer, who was in his fifth term as Sonoma County Physician when accusations were made against him by two of his subordinates, nurses of the Sonoma County Hospital.

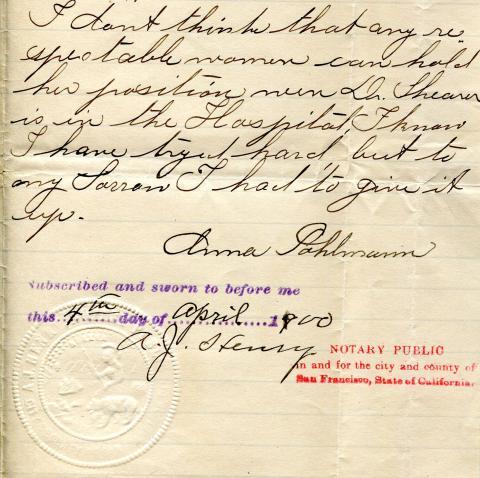

The first nurse, 33-year-old Anna Pohlmann, worked as a matron at the county hospital from July 1899 to March 1900 and told her pastor of the treatment she received from Dr. Shearer, charging him with improper conduct toward her that had caused her to resign from her position. She further confided in the pastor that another nurse, Bertha Sundell, had also been compelled to resign for the same reason. The pastor then presented their complaints to the Santa Rosa Ministerial Union, an organization comprised of all the ministers of Santa Rosa. A committee was appointed to oversee the matter and told the nurses that their “unsupported statements amounted to but little and could not be recognized by [the union] unless they were put in the form of affidavits” (Statement by members of the Ministerial Union of Santa Rosa presented to the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, 8 May 1900). The women obliged, and these handwritten affidavits, along with the statement by the Ministerial Union, were recently discovered by one of our volunteers who was sorting a box of miscellaneous Board of Supervisor records pulled from the Sonoma County Archives and brought to the Library.

A search of newspapers at the turn of the century reveals headlines such as “Scandal in a Hospital. The County Physician of Sonoma Accused by Nurses. Said to have paid them obnoxious attentions. Attendants declare that they were obliged to leave their positions” (SF Chronicle, 9 May 1900). Polhmann’s affidavit reveals her anguish: “Dr. Shearer has insulted me wenever [sic] he got a chance. If I had to buy anything for the Hospital, I always had to go to the Dr. Office for an order and he would invariable [sic] ask me to come up and spend the evening or even to stay all night with him in his office.” Sundell said it was her duty to tell of her experiences so that no other girl would be ruined:

He insisted on wanting to send out a buggy in the evening so I could come in and stay and spend the evening with him in his office. He several times during his visits at the Hospital sent out the other nurses in order to get a chance to insult me.

I liked it very much at the hospital but I could not put up with the Doctor any longer and the end would have been that he would have discharged me because I did not submit to his wishes and no woman with a pure character could keep the place but in order too would have to either be a corrupt woman or turn one.

On May 10, 1900, in the presence of the Board of Supervisors, members of the Ministerial Union, and a large crowd of interested citizens, Dr. Shearer flatly denied the charges against him. It is no surprise that his strategy to defend himself was to attack the character of Anna Pohlmann. One witness testified of her intemperance at work. Shearer claimed she sought revenge because he had discharged her from the hospital for intoxication. He also accused members of the Ministerial Union of personal bias against him. The final decision to exonerate the doctor of all charges was swiftly made with a vote of three “ayes” and one refusal. Supervisor Austin refused to vote because the Board had declined to postpone action in order to give Nurses Pohlmann and Sundell an opportunity to be heard in their own defense.

Dr. Shearer died five years later on 28 May 1905. He had served as a surgeon in the Union Army during the Civil War. In what was described as a moving eulogy at the Santa Rosa Lodge of Elks, Attorney Allison B. Ware paid tribute to “the deceased’s love of fellow man and his desire to assist the afflicted.”

Anna and Bertha disappear from the papers immediately following these events. Anna continued to work as a nurse after moving to Vallejo. They had had nothing to gain by speaking out but everything to lose. It must have taken immense courage to have gone public with their personal stories, shaming such a well-known and respected community leader, who had been repeatedly reelected by the very Board deciding the case. Because of their brave act, these women’s testimonies survive as part of the public record and have finally seen the light of day.

This is just one of the many personal stories hidden in the records of the Archives waiting to be discovered and illuminated…perhaps by you.